PORCELAIN PLATES.NET A Website for Porcelain License Plate Collectors & Enthusiasts |

Pennsylvania Archive - Part 1

TOTAL KNOWN PORCELAIN VARIETIES: 56

I: PRE-STATES / CITY & COUNTY PLATES

BANGOR

One of the relatively few Pennsylvania cities that issued porcelain license plates

was Bangor, which licensed teamsters with small annual porcelain plates

between about 1914 and 1923, although not all years are known. A Borough of

Northampton County, Bangor lies 45 miles Southeast of Scranton in the Eastern

part of the state, near the border with New Jersey. It owes its existence to the

discovery and successful commercial exploitation of slate quarries in the region.

It was home to some 5,000 residents when the teamster licenses were issued.

These little plates are extremely rare and are the only example of porcelain

license plates I've seen bearing the term "Teamster."

PHILADELPHIA

A number of Pennsylvania cities issued

porcelain city plates, but only Philadelphia

began the issuance of plates in the state’s

pre-state era. As one of the oldest, largest,

and most historically significant cities in

the United States, this comes as no

surprise. One of the major commercial and

cultural centers on the East Coast,

Philadelphia boasted a population of more

than 1,300,000 residents when plates were

first issued there. The city first passed

legislation on December 26, 1902 requiring

vehicles to display license plates to be

furnished by the Bureau of Boiler

Inspection. In fact, the dated 1903 first

Philadelphia issue is notable for being the

earliest dated porcelain license plate of

any kind known. The registration fee was

$2.00 for the first year and $1.00 for

renewals each year thereafter. As the

ordinance read, each vehicle "shall always

display or cause to be displayed in a prominent and conspicuous part of said

vehicle, to be determined by the said Bureau of Boiler Inspection, a sign seven

inches long and four inches wide; to be furnished by the said Bureau of Boiler

Inspection, bearing the license number of its driver." According to the Iowa City,

IA “Daily Press,” there were 1,663 licenses granted by the city of Philadelphia in

1903, and 2,340 in 1904.

It is unclear who manufactured the 1903 plates, but we have newspaper

documentation that the 1904 issues were produced by the Ingram-Richardson

Company of Beaver Falls, PA. Interestingly, an explosion in Ing-Rich's plant

caused a delay and the plates did not get to Philadelphia on time. There is

evidence that the 1905 plates began at #101, and based on the fact that there are

no surviving examples of any Philadelphia porcelains under three digits, it seems

safe to presume that this method of numbering was used for the entire run.

The city continued its practice of annual porcelain city issues for four years, until

they ceased issuance at the end of 1906, one year after the state took over. This

transition was not a smooth one, however, and the issue was actually decided in

court. The issue at hand was the new Pennsylvania state law which declared that

"not more than one state license number shall be carried upon the front and back

of the said vehicle... and a license number obtained in any other place or state

shall be removed from said vehicle while the vehicle is being used within this

commonwealth." Based on this language in the law, the Philadelphia Automobile

Club contended that the city ordinance was unjust and applied for an injunction

to prevent the city from compelling vehicle owners to take out 1906 licenses.

Late in 1905, the court of Common Pleas took up the case and denied the

injunction, ruling instead that the city did indeed have a right to charge a local

license fee and regulate automobiles for the safety of its citizens. Undeterred,

the Automobile Club appealed to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

This was an important early test case for automobilists who resented any taxation

on their vehicles and considered the simultaneous state and city ordinances to

be unjust double taxation. Word of the court challenge was reported in papers as

far away as Colorado Springs. The “Saturday News” of Frederick, MD reported on

December 30 that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court would be considering the

matter and that the city of Philadelphia was restricted from issuing licenses until

the case was heard. For nearly three months, automobiles in Philadelphia were

free to run the streets without city plates. In arguments before the Supreme

Court on March 23rd, Pennsylvania Attorney General Hampton L. Carson argued

his case, saying "on the field of battle a general officer supersedes a colonel, and

when a superior appears the general officer is superseded. When Congress

passed a national bankruptcy law all state bankruptcy laws were suspended. In

the same way the state automobile law supersedes the city ordinance."

The Court took the matter under advisement, but on May 14th, the decision

rendered by the Court of Common Pleas was sustained. The ruling of the

Supreme Court found that the language of the new state law did not prohibit

licensing by cities within Pennsylvania. The fact that the ordinance read "not

more than one state license number shall be carried" did not apply to city issues,

and the wording indicating that "a license number obtained in any other place"

was referring to foreign countries rather than local jurisdictions. "We have

reached the conclusion," wrote the court, "that the injunction prayed for must be

refused."

With the final word on the matter finally spoken, vehicle owners in the city of

Philadelphia from that point forward were compelled to carry both state and city

plates. One aspect of the 1906 plates is that they are marked on the reverse with

the signature hand-dating system of the Baltimore Enamel and Novelty Company,

which manufactured them. All known plates are marked "125," indicating a date of

manufacture of December, 1905. Thus, these plates were at least ordered, if not

received, by the city already when this matter went to court and sat gathering

dust while the issue played out. Based on plate numbers, there is a precipitous

drop in the number of registrations that year compared to 1905. Whereas

approximately 3,800 1905 plates were issued, the highest known 1906 is #2,500.

This is likely due to the litigation-induced delay in issuing the plates and the fact

that they were only used for the last seven months of the year. Numerous

potential registrants who would have normally received plates from January

through May would have changed their minds, wrecked their cars, moved out of

the city, or perhaps just chosen to risk arrest for the remainder of the year. Had

the court case not reared its ugly head, the city would probably have needed to

order additional plates from Ing-Rich later in the year to supplement its initial

order. Under the circumstances, however, it appears this was not necessary and

that the first order of 2,500 or so plates was more than sufficient.

Philadelphia porcelains are surprisingly easy to acquire. The 1903 is the hardest,

but even here we can estimate that some 25-30 of them are known in collectors'

hands. Perhaps 50 1904 plates are known, and maybe 75 or so 1905s. 1906 plates

are slightly rarer again - about on par with the 1904 issue - because of their

limited time of issuance.

Interestingly, the city of Philadelphia also issued a long series of porcelain

vendor plates, first beginning in 1905 and stretching all the way through 1914.

Based on date codes on the reverse, we know that the 1906 and 1909 plates were

produced by the Baltimore Enamel and Novelty Company, but the manufacturer of

the remainder of these issues remains a mystery. This 10 year span of plates

surpasses the Bangor Teamsters Licenses as the longest run of porcelain plates

to be issued by any jurisdiction in Pennsylvania. These plates likely went on non-

motorized vendor carts, although we don't know this for sure. Although these

little plates are very rare, numbers are known to have reached nearly 3,000. It is

perhaps worth noting that for the first nine years, these plates used the term

"Vender," but in the final year of issuance the spelling was changed to "Vendor."

PITTSBURGH

The County Seat of Allegheny County in Western Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh was a

major American city in the porcelain era. In 1901, the U.S. Steel Corporation

formed, and Pittsburgh’s prosperity and population took off. A decade later,

between a third and a half of the nation's various types of steel were being

produced there. It was during this phenomenal growth that the city's four

porcelain plates were issued. The ordinance was actually first passed in March of

1905, providing that "every vehicle... shall always display or cause to be displayed

in a prominent and conspicuous part on the rear of said vehicle a license plate to

be furnished by the said city treasurer bearing the license number." However, in

spite of this ordinance, full plates had never been issued. Instead, it appears

that small dashboard discs or something equivalent had been used. This

changed in 1908 when the city finally began issuing porcelain license plates.

One fascinating aspect of the Pittsburgh licenses is that they were issued in two

distinct varieties each year. As a March, 1908 article in "The Horseless Age"

reveals, the blue 1908 plates were used on vehicles with one seat, while the gray

(or "slate," according to the article) version was used for two-seated

automobiles. Similarly, plate historian Eric Tanner has a photocopy of a brown

Pittsburgh 1909 porcelain #13 along with its matching certificate showing that the

plate was issued to a one-seated automobile for a fee of $6.00. Thus, the light

green 1909 plates were for two-seated vehicles.

Pittsburgh plates are often thought of in the same vein as Philadelphia

porcelains. However, they bear no resemblance in terms of rarity. Whereas

Philadelphia plates are relatively attainable, Pittsburgh porcelains are incredibly

scarce. I've documented eight known numbers of the brown 1909 plate, and with

eight survivors, this is the most common of the four! The blue 1908 plates appear

to have reached the mid 100s in number, while the gray 1908 plates neared 500.

In 1909, the pale green plates are known into the mid 600s, and the brown version

up to nearly 1,200. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court's defeat of the Philadelphia

Auto Club's proposed injunction against city-issued plates in that city in 1906

opened the way for cities such as Pittsburgh to their own licenses. It is unclear

why Pittsburgh ceased this practice after only two years.

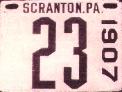

SCRANTON

Nestled in the Lackawanna River Valley in Northeastern Pennsylvania, Scranton

was in important Pennsylvania city in the early 20th century. In 1900, the city’s

population surpassed the 100,000 mark, making it one of the 40 most populous

cities in the U.S. Although the city made its mark with iron, the turn of the century

saw coal take off as the city’s main industry. In 1907, the city issued its first and

only porcelain license plate, of which five examples survive in collectors' hands

today. Although the numbers and letters appear black, they are actually a very

dark blue. Just like the Pennsylvania state issues in 1907, the Scranton plates

were manufactured by the Ingram-Richardson Manufacturing Company of Beaver

Falls, PA and are precisely the same size as four digit 1907 state plates. Not only

are the Scranton porcelains the earliest known city issues manufactured by Ing-

Rich, but they are the only known city plates made by that company until 1916. I

am aware of a half-dozen surviving examples of these elusive porcelains with

numbers reaching into the low 100s.

SEWICKLEY

Sewickley is a township in the greater Pittsburgh area, lying on the Ohio River. A

single porcelain license plate is known from the city – a dated 1909 issue which is

smaller in size than any other Pennsylvania porcelain.

I: PRE-STATES / CITY & COUNTY PLATES

BANGOR

One of the relatively few Pennsylvania cities that issued porcelain license plates

was Bangor, which licensed teamsters with small annual porcelain plates

between about 1914 and 1923, although not all years are known. A Borough of

Northampton County, Bangor lies 45 miles Southeast of Scranton in the Eastern

part of the state, near the border with New Jersey. It owes its existence to the

discovery and successful commercial exploitation of slate quarries in the region.

It was home to some 5,000 residents when the teamster licenses were issued.

These little plates are extremely rare and are the only example of porcelain

license plates I've seen bearing the term "Teamster."

PHILADELPHIA

A number of Pennsylvania cities issued

porcelain city plates, but only Philadelphia

began the issuance of plates in the state’s

pre-state era. As one of the oldest, largest,

and most historically significant cities in

the United States, this comes as no

surprise. One of the major commercial and

cultural centers on the East Coast,

Philadelphia boasted a population of more

than 1,300,000 residents when plates were

first issued there. The city first passed

legislation on December 26, 1902 requiring

vehicles to display license plates to be

furnished by the Bureau of Boiler

Inspection. In fact, the dated 1903 first

Philadelphia issue is notable for being the

earliest dated porcelain license plate of

any kind known. The registration fee was

$2.00 for the first year and $1.00 for

renewals each year thereafter. As the

ordinance read, each vehicle "shall always

display or cause to be displayed in a prominent and conspicuous part of said

vehicle, to be determined by the said Bureau of Boiler Inspection, a sign seven

inches long and four inches wide; to be furnished by the said Bureau of Boiler

Inspection, bearing the license number of its driver." According to the Iowa City,

IA “Daily Press,” there were 1,663 licenses granted by the city of Philadelphia in

1903, and 2,340 in 1904.

It is unclear who manufactured the 1903 plates, but we have newspaper

documentation that the 1904 issues were produced by the Ingram-Richardson

Company of Beaver Falls, PA. Interestingly, an explosion in Ing-Rich's plant

caused a delay and the plates did not get to Philadelphia on time. There is

evidence that the 1905 plates began at #101, and based on the fact that there are

no surviving examples of any Philadelphia porcelains under three digits, it seems

safe to presume that this method of numbering was used for the entire run.

The city continued its practice of annual porcelain city issues for four years, until

they ceased issuance at the end of 1906, one year after the state took over. This

transition was not a smooth one, however, and the issue was actually decided in

court. The issue at hand was the new Pennsylvania state law which declared that

"not more than one state license number shall be carried upon the front and back

of the said vehicle... and a license number obtained in any other place or state

shall be removed from said vehicle while the vehicle is being used within this

commonwealth." Based on this language in the law, the Philadelphia Automobile

Club contended that the city ordinance was unjust and applied for an injunction

to prevent the city from compelling vehicle owners to take out 1906 licenses.

Late in 1905, the court of Common Pleas took up the case and denied the

injunction, ruling instead that the city did indeed have a right to charge a local

license fee and regulate automobiles for the safety of its citizens. Undeterred,

the Automobile Club appealed to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

This was an important early test case for automobilists who resented any taxation

on their vehicles and considered the simultaneous state and city ordinances to

be unjust double taxation. Word of the court challenge was reported in papers as

far away as Colorado Springs. The “Saturday News” of Frederick, MD reported on

December 30 that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court would be considering the

matter and that the city of Philadelphia was restricted from issuing licenses until

the case was heard. For nearly three months, automobiles in Philadelphia were

free to run the streets without city plates. In arguments before the Supreme

Court on March 23rd, Pennsylvania Attorney General Hampton L. Carson argued

his case, saying "on the field of battle a general officer supersedes a colonel, and

when a superior appears the general officer is superseded. When Congress

passed a national bankruptcy law all state bankruptcy laws were suspended. In

the same way the state automobile law supersedes the city ordinance."

The Court took the matter under advisement, but on May 14th, the decision

rendered by the Court of Common Pleas was sustained. The ruling of the

Supreme Court found that the language of the new state law did not prohibit

licensing by cities within Pennsylvania. The fact that the ordinance read "not

more than one state license number shall be carried" did not apply to city issues,

and the wording indicating that "a license number obtained in any other place"

was referring to foreign countries rather than local jurisdictions. "We have

reached the conclusion," wrote the court, "that the injunction prayed for must be

refused."

With the final word on the matter finally spoken, vehicle owners in the city of

Philadelphia from that point forward were compelled to carry both state and city

plates. One aspect of the 1906 plates is that they are marked on the reverse with

the signature hand-dating system of the Baltimore Enamel and Novelty Company,

which manufactured them. All known plates are marked "125," indicating a date of

manufacture of December, 1905. Thus, these plates were at least ordered, if not

received, by the city already when this matter went to court and sat gathering

dust while the issue played out. Based on plate numbers, there is a precipitous

drop in the number of registrations that year compared to 1905. Whereas

approximately 3,800 1905 plates were issued, the highest known 1906 is #2,500.

This is likely due to the litigation-induced delay in issuing the plates and the fact

that they were only used for the last seven months of the year. Numerous

potential registrants who would have normally received plates from January

through May would have changed their minds, wrecked their cars, moved out of

the city, or perhaps just chosen to risk arrest for the remainder of the year. Had

the court case not reared its ugly head, the city would probably have needed to

order additional plates from Ing-Rich later in the year to supplement its initial

order. Under the circumstances, however, it appears this was not necessary and

that the first order of 2,500 or so plates was more than sufficient.

Philadelphia porcelains are surprisingly easy to acquire. The 1903 is the hardest,

but even here we can estimate that some 25-30 of them are known in collectors'

hands. Perhaps 50 1904 plates are known, and maybe 75 or so 1905s. 1906 plates

are slightly rarer again - about on par with the 1904 issue - because of their

limited time of issuance.

Interestingly, the city of Philadelphia also issued a long series of porcelain

vendor plates, first beginning in 1905 and stretching all the way through 1914.

Based on date codes on the reverse, we know that the 1906 and 1909 plates were

produced by the Baltimore Enamel and Novelty Company, but the manufacturer of

the remainder of these issues remains a mystery. This 10 year span of plates

surpasses the Bangor Teamsters Licenses as the longest run of porcelain plates

to be issued by any jurisdiction in Pennsylvania. These plates likely went on non-

motorized vendor carts, although we don't know this for sure. Although these

little plates are very rare, numbers are known to have reached nearly 3,000. It is

perhaps worth noting that for the first nine years, these plates used the term

"Vender," but in the final year of issuance the spelling was changed to "Vendor."

PITTSBURGH

The County Seat of Allegheny County in Western Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh was a

major American city in the porcelain era. In 1901, the U.S. Steel Corporation

formed, and Pittsburgh’s prosperity and population took off. A decade later,

between a third and a half of the nation's various types of steel were being

produced there. It was during this phenomenal growth that the city's four

porcelain plates were issued. The ordinance was actually first passed in March of

1905, providing that "every vehicle... shall always display or cause to be displayed

in a prominent and conspicuous part on the rear of said vehicle a license plate to

be furnished by the said city treasurer bearing the license number." However, in

spite of this ordinance, full plates had never been issued. Instead, it appears

that small dashboard discs or something equivalent had been used. This

changed in 1908 when the city finally began issuing porcelain license plates.

One fascinating aspect of the Pittsburgh licenses is that they were issued in two

distinct varieties each year. As a March, 1908 article in "The Horseless Age"

reveals, the blue 1908 plates were used on vehicles with one seat, while the gray

(or "slate," according to the article) version was used for two-seated

automobiles. Similarly, plate historian Eric Tanner has a photocopy of a brown

Pittsburgh 1909 porcelain #13 along with its matching certificate showing that the

plate was issued to a one-seated automobile for a fee of $6.00. Thus, the light

green 1909 plates were for two-seated vehicles.

Pittsburgh plates are often thought of in the same vein as Philadelphia

porcelains. However, they bear no resemblance in terms of rarity. Whereas

Philadelphia plates are relatively attainable, Pittsburgh porcelains are incredibly

scarce. I've documented eight known numbers of the brown 1909 plate, and with

eight survivors, this is the most common of the four! The blue 1908 plates appear

to have reached the mid 100s in number, while the gray 1908 plates neared 500.

In 1909, the pale green plates are known into the mid 600s, and the brown version

up to nearly 1,200. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court's defeat of the Philadelphia

Auto Club's proposed injunction against city-issued plates in that city in 1906

opened the way for cities such as Pittsburgh to their own licenses. It is unclear

why Pittsburgh ceased this practice after only two years.

SCRANTON

Nestled in the Lackawanna River Valley in Northeastern Pennsylvania, Scranton

was in important Pennsylvania city in the early 20th century. In 1900, the city’s

population surpassed the 100,000 mark, making it one of the 40 most populous

cities in the U.S. Although the city made its mark with iron, the turn of the century

saw coal take off as the city’s main industry. In 1907, the city issued its first and

only porcelain license plate, of which five examples survive in collectors' hands

today. Although the numbers and letters appear black, they are actually a very

dark blue. Just like the Pennsylvania state issues in 1907, the Scranton plates

were manufactured by the Ingram-Richardson Manufacturing Company of Beaver

Falls, PA and are precisely the same size as four digit 1907 state plates. Not only

are the Scranton porcelains the earliest known city issues manufactured by Ing-

Rich, but they are the only known city plates made by that company until 1916. I

am aware of a half-dozen surviving examples of these elusive porcelains with

numbers reaching into the low 100s.

SEWICKLEY

Sewickley is a township in the greater Pittsburgh area, lying on the Ohio River. A

single porcelain license plate is known from the city – a dated 1909 issue which is

smaller in size than any other Pennsylvania porcelain.

|

|

|

|

Due to the size of the Pennsylvania archive, I have split it into two parts. Part 2 contains information on the following: II: STATE-ISSUED PASSENGER PLATES III: STATE-ISSUED NON-PASSENGER PLATES IV: ODDBALL PORCELAINS FURTHER READING CLICK HERE FOR PART 2 OF THE PENNSYLVANIA ARCHIVE |

|

|

The Colorado Springs Gazette, December 19, 1905 |

| Baltimore Enamel & Novelty Company's date of manufacture mark (Dec., 1905) on reverse of Philadelphia 1906 issue. |

| Matching 1903 Philadelphia Operator's License and Receipt Card |

| The Automobile (Chicago), March 29, 1906 |

| Announcement of new 1905 Philadelphia porcelains |

| Following the Supreme Court decision regarding 1906 plates, newspapers alerted motorists to their need to carry both state and city plates. |

| The Horseless Age, May 23, 1906 |

| The Horseless Age, March 4, 1908 |

| Motor Age January 12, 1905 |