PORCELAIN PLATES.NET A Website for Porcelain License Plate Collectors & Enthusiasts |

40 Years of Porcelain License Plates

In the earliest days of motoring, automobile ownership was a mark of distinction

and wealth. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, automobiles were largely

still a flight of fancy obsessed over by entrepreneurs and scientists, but they

quickly became a reality. By the turn of the century, commercially manufactured

vehicles were now available, but they remained a luxury item that few could

afford. Bought by the adventurous gentry, automobiles were more for sport than

transportation. The infrastructure was not yet set up, roads remained unpaved,

and industries set up to service and repair vehicles were in their infancy. In

these early years, vehicles were a part of an owner’s very identity, and everyone

in town knew who owned which cars.

However, the motoring elite quickly developed a reputation nationwide for

recklessness and disregard for the safety of others. Newspapers in the first

decade of the 20th century were filled with reports of injuries and deaths caused

by speeding drivers. Horses were spooked, riders were thrown, and pedestrians

were run down - and the drivers usually got away with it. The idea of placing

license plates on cars grew from this brewing resentment towards the

"automobilists," as they were known. Cities and states across the country were

soon passing laws regulating the speed of automobiles, the equipment they were

required to carry, the roads they were and weren't allowed to use, etc. And to

ensure that these new laws were not ignored - cars began to be licensed and

"tagged."

Of course, finicky vehicle owners were not at all pleased with the crusade against

them and their "devil wagons" as the press frequently labeled automobiles.

Placing a license number on a car was thought to be a disfigurement - a lowbrow

gesture which would reduce the appearance of the vehicle and make it look like

a common taxi. However, as more and more automobiles filled the streets of

America, it was clear that the automobilists were fighting a losing battle and their

vehicles would soon be regulated, licensed, and tagged in spite of their

objections. At first, the numbers placed on cars were crude, sometimes written

right on the vehicle, although more commonly fashioned by the owner out of

metal, leather, or wood. Department stores began to offer house numbers and

leather or metal pads.

The 1900s

Of course, cities, counties, and states quickly realized that the automobile was

here to stay and wanted a piece of the revenue, and the era of the homemade

plate soon gave way to standardized official issues. This change began in New

England in 1903, when Massachusetts issued its first porcelain license plates to

vehicle registrants with an attractive, undated plate designed to be used for the

next five years. Porcelain manufacturing for signs and kitchenware had been

around since the middle of the previous century, so the application to license

plates was not as much of a stretch as one might at first think. Rather than being

an expensive high-class accessory befitting the motoring elite, porcelain license

plates were actually a very logical choice. Effective metal stamping was still a

decade away and porcelain manufacturing had been perfected and required no

skilled labor. With this first Massachusetts plate, the era of the porcelain license

plates had begun. That same year, the city of Philadelphia issued a dated

porcelain plate – the earliest dated porcelain ever made.

The state and city issuance of license plates caught on, and porcelain continued

to be the material of choice. It quickly spread throughout the Northeast. By 1905,

every state in New England had begun issuing porcelain plates. A number of

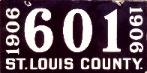

cities jumped on the bandwagon as well in this first decade of the century. St.

Louis and St. Louis County began issuing porcelain plates in 1904 and 1906,

respectively. Philadelphia continued issuing porcelains through 1906, at which

time the state of Pennsylvania took over with their own porcelain issues. In 1906,

the state of Virginia also issued an undated porcelain plate. West Virginia began

issuing porcelains in 1907, as did the cities of Scranton, PA; Louisville, KY; and

Columbus, OH. Pittsburgh, PA and Warren, OH followed suit in 1908, as did the

state of Ohio which issued an undated multi-year plate. Although we are

uncertain of whether it is a vehicle license, a porcelain Chicago “roofer” plate

dated 1908 also exists. A long series of vendor, huckster, cartman, peddler,

scavenger, and milk licenses believed to have been issued by the city of

Rochester, NY also began in at least 1907. And although undated, porcelain

plates from both Providence, RI and Lorain, OH are also believed to have been

issued in the first decade of the century.

Delaware caught the porcelain bug in 1909 with the first of 7 annual dated issues

from the state, and although New Jersey had begun issuing plates in 1908, 1909

was the first year they issued porcelains. Plates from jurisdictions such as

Sewickley, PA; Catlettsburg and Newport, KY; and the first of a run of at least 6

annual issues from Wheeling, WV are also known from 1909. In fact, 1909 was a

banner year in the issuance of porcelains. Ottawa, KS; Little Rock and Fort Smith,

AR; and Birmingham, Mobile and Montgomery, AL all launched their respective

states into the porcelain era in 1909. The trend of issuing porcelain plates had

reached the Deep South and would soon spread Westward. By the end of 1909,

twelve states were issuing porcelain license plates, and some twenty cities and

counties had experimented with porcelains as well. The coming decade would

see the era of porcelain license plates rise sharply, reach it’s peak, and decline

to a mere shadow of its former self.

The 1910s

The dawn of the second decade of the 20th Century saw numerous cities,

counties, and states taking up the trend of issuing porcelain license plates to

vehicle registrants. That year, the states of Kentucky, Michigan and Maryland

began their runs of state-issued plates. In Michigan and Kentucky, all varieties of

plates were porcelain, while in Maryland, only the dealer plates were. Cities

jumping on the porcelain bandwagon in 1910 included Hailey, ID; Valley City, ND;

Tulsa, OK; Jacksonville, FL; and Moundsville, WV. With the exception of the

Moundsville plate, interestingly, each of these cities pioneered their respective

state’s experimentation with porcelain plates. Again with the exception of the

Moundsville, none of the states from which these plates were issued ever took

up the task of issuing porcelain license plates themselves, instead leaving the

issuance of such plates up to individual cities. Pine Bluff, AR, as well as

Covington, Lexington and Paducah, KY also began issuing porcelains in 1910.

This decade also seems to have brought about the proliferation of porcelain non-

passenger varieties as well. In Michigan, porcelains were issued to passenger

vehicles, manufacturers, motorcycles, and motorcycle manufacturers in 1910.

After four years of porcelain plates, both Pennsylvania and Virginia also

introduced non-passenger porcelains in 1910 with dealer issues. That same year,

the state of Connecticut introduced livery porcelains, while the city of New Britain

began issuing porcelain plates to the city’s milk dealers. But in spite of this

obvious rise in the issuance and varied usage of porcelain license plates, there

was still not a single state West of the Mississippi that was issuing porcelains of

its own in 1910.

The demand for affordable automobiles was growing with each passing year as

the utility of the automobile was becoming increasingly apparent. In 1913 Henry

Ford introduced the assembly line to automobile manufacturing and changed

motoring forever. No longer was automobile ownership the elite symbol it once

was, as more and more Americans found ways to afford cars which were now

more quickly and cheaply manufactured. Before long, many states would

abandon their issuance of porcelain plates in favor of more cheaply made flat or

embossed metal plates.

But the porcelain era was not dead yet, and in fact, would reach new heights

between 1910 and 1915. In fact, in that 6 year span, 60% of all the state-issued

passenger porcelains ever produced were issued. 1911 saw officially-issued

porcelain license plates spread North to Canada, where the Provinces of Ontario,

Manitoba, and New Brunswick all began their official runs with porcelain plates.

In the U.S., the state of Arkansas also chose porcelain as the material for its first

state-issued license plate. The very first porcelain plates from neighboring

Louisiana also appeared in 1911 as the cities of Alexandria and Monroe began

issuing porcelains. Other cities first issuing plates in 1911 include University City

and Kansas City, MO, as well as Cordell, OK. The earliest dated Mississippi plate

is also a porcelain from 1911, although it is unclear whether this is a pre-state,

some sort of prototype, or perhaps even the state’s first issue. Meanwhile, every

state that had begun issuing porcelain plates at any time prior to this was still

issuing porcelains.

In 1912, cities in Alabama ceased the issuance of porcelain plates and the state

took over with its first of four annual issues. This was also the single year the

state of New York experimented with porcelains, with a large, undated red &

white plate. In Canada, both Alberta and Saskatchewan began their Provincial

runs with dated 1912 plates. In Kansas, the cities of Kansas City and Wichita each

issued their first porcelains in 1912 as well, as did New Orleans, LA; Dayton, OH;

Dewey, OK; Independence, MO; and Morgantown, WV. When looking at only

official state issued porcelain passenger plates, 1913 was the single peak year in

the history of porcelain plates. In this year, 19 different states were issuing

porcelain plates. These states were still clustered in the Northeast, but reached

into the Deep South states of Alabama and Arkansas and as far west as Colorado.

In fact, Colorado’s first-issue 1913 plate made it the first state West of Minnesota

to officially issue porcelains. Indiana and North Carolina also kicked off their

respective state runs with porcelain plates in 1913. Cities joining the porcelain

fray in 1913 included Caney, KS; St. Joseph, MO; Nowata, OK; and Lima, OH. This

was also the first year of relatively long runs of plates from both Manchester,

New Hampshire and Hamilton, Ontario.

1914 & 1915 would also see substantial, wide-spread use of porcelain plates, but

technically, the decline had already begun. 1914 saw porcelain plates finally

reach the West coast as the state of California began issuing plates. Further

North, Seattle, Washington began issuing porcelain plates to commercial vehicles

that same year. 1914 also saw the first issuance of porcelains from places as

diverse as Stamford, CT; Worcester, MA; Rochester, NY; Bangor, PA; Memphis,

TN; Clifton Forge, VA; and the Oklahoma cities of Bigheart, Chickasha, Okmulgee,

and Shawnee. The city of Shreveport, LA and the Louisiana Parishes of St. John

and St. Mary also issued their first and only known porcelains in 1914.

Three states dropped out of the official state-issued porcelain license plate

business in 1914 and two more in 1915. By 1915, in fact, the numbers had

dropped to 1910 levels and 1916 would see a precipitous drop even further as all

but six states abandoned the use of official state porcelains. In this last of the

peak years from 1910-1915, however, porcelains remained popular. Although no

new states or provinces adopted porcelains that year, cities and counties across

North America continued to utilize porcelain. In fact, porcelain jumped more than

2,000 miles to the West as the Hawaiian counties of Hawaii and Honolulu both

began issuing porcelains. Cities such as Ponchatoula, LA; Clinton, MA; Fairmont,

WV; and both Collinsville and Sapulpa in Oklahoma also issued their first

porcelains this year. By the end of 1915, 90% of all the state issued porcelains

ever produced had been made.

In 1916, 9 states that had been issuing porcelain plates the year before ceased

doing so. Interestingly, however, one state that had never before experimented

with porcelains took a shot with a single issue in 1916. This was the state of

Wyoming which decided the next year to go back to embossed metal plates. For

the next 7 years, the state issuance of porcelain license plates dwindled to a

mere trickle before ending altogether. In 1917, North Carolina abandoned

porcelain for embossed metal. In 1918, Rhode Island issued its first non-

porcelain plate in 14 years. And in 1919, the New England states were finally

porcelain-free as New Hampshire became the last hold-out to switch to metal.

The 1920s

The dawn of the 1920s saw two last-ditch efforts to adopt porcelain in the West,

as the states of New Mexico and Washington experimented with the material. But

like Wyoming four years earlier, one year was enough for Washington, and the

state was back to embossed metal by 1921. New Mexico, however, maintained its

confidence in porcelain, issuing plates for four years. The sole torch bearer for

state-issued porcelains once Washington dropped out, New Mexico carried on

the tradition through 1923 when they finally abandoned porcelain for good. The

era of the state-issued porcelain license plate was now over.

City and county issued porcelains were changing as well. The time when local

plates would adorn all of the passenger vehicles in a given city, town, or county

had now passed. Alexandria, Louisiana’s long run of 10 annual issues ceased in

1920. Kansas City, Missouri’s last porcelain plates for automobiles and

motorcycles also came in 1920. And that same year, the final porcelains were

issued by Memphis, Tennessee before the city switched to metal plates. Bisbee,

Arizona’s two year run of porcelains ended the following year in 1921, the same

year that Honolulu issued a porcelain motorcycle plate, marking the last Hawaiian

porcelain of any kind. Other porcelain runs were ending as well. Manchester,

New Hampshire’s 10-year stretch of annual Garbage plates stopped in 1922. The

Teamsters licenses issued by Bangor, Pennsylvania since 1914 finally ceased in

1923. And North Carolina’s rich tradition of city and county issued plates came to

a virtual standstill in 1926. However, porcelain license plates would manage to

hang on for a while longer with a much reduced selection of local issues which

were becoming more and more specialized.

Among the porcelains introduced in the 1920s were Junkman plates from

Stamford, Connecticut; Motor Bus plates from Fall River, Massachusetts; and

Licensed Trucking plates from Providence, Rhode Island. Clearly, the use of

porcelain for license plates was fast becoming a thing of the past. As the decade

wore on, fewer and fewer porcelain license plates would be used.

The 1930s

While there were literally hundreds of different varieties of porcelain license

plates being issued by states, provinces, cities, and counties throughout the U.S.

and Canada in 1915, just 15 years later in 1930, I can only document a grand total

of four porcelain license plates of any kind. Only a few cities were clinging to

porcelain at this late stage, with runs continuing into the 1930s from Worcester,

MA; Wilson, NC; and Providence, RI. The group of plates thought by most to be

from Rochester, NY also continued the issuance of Milk Licenses into the 1930s.

The only two cities known to have introduced any type of porcelain license plate

during this decade were Sacramento, California, which began issuing Wholesale

Produce Dealer plates in 1935, and Schenectady, New York which began the

issuance of Milk Licenses mid-year. In 1937, the 20+ year run of porcelain plates

privately issued to motorists using the Long Island Motor Parkway finally came to

an end, and the end to porcelain license plates altogether was only 10 years off.

The 1940s

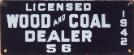

The only city-issued porcelain license plates in use in the 1940s were Produce

Dealer and Wood & Coal Dealer plates from Sacramento, CA; Milk Permit plates

from Bristol, CT; and Licensed Trucking and Hackney Carriage plates from

Providence, RI – none of which appear to have continued past 1942. With the

demise of the Providence plates that year, New England’s uninterrupted 40-year

run of porcelain license plates dating back to 1903 finally came to and end.

Beyond these few city issues, Delaware brought porcelain plates back to the

state for the first time since 1915. Issued from 1942 through 1947, these were

multi-year base plates designed to be revalidated annually with metal date tabs.

With the re-introduction of Delaware porcelains, this was the first time a state or

provincially issued porcelain license plate had been used since 1923. Surely we

will find odd porcelains from the 1940s here and there as time goes on, such as

the toppers used by vehicles at the West Point military academy from the mid

1930s until at least 1940, but by the end of World War II, the death knell for

porcelain license plates had been sounded. After 40 years, porcelain had

become a thing of the past.

and wealth. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, automobiles were largely

still a flight of fancy obsessed over by entrepreneurs and scientists, but they

quickly became a reality. By the turn of the century, commercially manufactured

vehicles were now available, but they remained a luxury item that few could

afford. Bought by the adventurous gentry, automobiles were more for sport than

transportation. The infrastructure was not yet set up, roads remained unpaved,

and industries set up to service and repair vehicles were in their infancy. In

these early years, vehicles were a part of an owner’s very identity, and everyone

in town knew who owned which cars.

However, the motoring elite quickly developed a reputation nationwide for

recklessness and disregard for the safety of others. Newspapers in the first

decade of the 20th century were filled with reports of injuries and deaths caused

by speeding drivers. Horses were spooked, riders were thrown, and pedestrians

were run down - and the drivers usually got away with it. The idea of placing

license plates on cars grew from this brewing resentment towards the

"automobilists," as they were known. Cities and states across the country were

soon passing laws regulating the speed of automobiles, the equipment they were

required to carry, the roads they were and weren't allowed to use, etc. And to

ensure that these new laws were not ignored - cars began to be licensed and

"tagged."

Of course, finicky vehicle owners were not at all pleased with the crusade against

them and their "devil wagons" as the press frequently labeled automobiles.

Placing a license number on a car was thought to be a disfigurement - a lowbrow

gesture which would reduce the appearance of the vehicle and make it look like

a common taxi. However, as more and more automobiles filled the streets of

America, it was clear that the automobilists were fighting a losing battle and their

vehicles would soon be regulated, licensed, and tagged in spite of their

objections. At first, the numbers placed on cars were crude, sometimes written

right on the vehicle, although more commonly fashioned by the owner out of

metal, leather, or wood. Department stores began to offer house numbers and

leather or metal pads.

The 1900s

Of course, cities, counties, and states quickly realized that the automobile was

here to stay and wanted a piece of the revenue, and the era of the homemade

plate soon gave way to standardized official issues. This change began in New

England in 1903, when Massachusetts issued its first porcelain license plates to

vehicle registrants with an attractive, undated plate designed to be used for the

next five years. Porcelain manufacturing for signs and kitchenware had been

around since the middle of the previous century, so the application to license

plates was not as much of a stretch as one might at first think. Rather than being

an expensive high-class accessory befitting the motoring elite, porcelain license

plates were actually a very logical choice. Effective metal stamping was still a

decade away and porcelain manufacturing had been perfected and required no

skilled labor. With this first Massachusetts plate, the era of the porcelain license

plates had begun. That same year, the city of Philadelphia issued a dated

porcelain plate – the earliest dated porcelain ever made.

The state and city issuance of license plates caught on, and porcelain continued

to be the material of choice. It quickly spread throughout the Northeast. By 1905,

every state in New England had begun issuing porcelain plates. A number of

cities jumped on the bandwagon as well in this first decade of the century. St.

Louis and St. Louis County began issuing porcelain plates in 1904 and 1906,

respectively. Philadelphia continued issuing porcelains through 1906, at which

time the state of Pennsylvania took over with their own porcelain issues. In 1906,

the state of Virginia also issued an undated porcelain plate. West Virginia began

issuing porcelains in 1907, as did the cities of Scranton, PA; Louisville, KY; and

Columbus, OH. Pittsburgh, PA and Warren, OH followed suit in 1908, as did the

state of Ohio which issued an undated multi-year plate. Although we are

uncertain of whether it is a vehicle license, a porcelain Chicago “roofer” plate

dated 1908 also exists. A long series of vendor, huckster, cartman, peddler,

scavenger, and milk licenses believed to have been issued by the city of

Rochester, NY also began in at least 1907. And although undated, porcelain

plates from both Providence, RI and Lorain, OH are also believed to have been

issued in the first decade of the century.

Delaware caught the porcelain bug in 1909 with the first of 7 annual dated issues

from the state, and although New Jersey had begun issuing plates in 1908, 1909

was the first year they issued porcelains. Plates from jurisdictions such as

Sewickley, PA; Catlettsburg and Newport, KY; and the first of a run of at least 6

annual issues from Wheeling, WV are also known from 1909. In fact, 1909 was a

banner year in the issuance of porcelains. Ottawa, KS; Little Rock and Fort Smith,

AR; and Birmingham, Mobile and Montgomery, AL all launched their respective

states into the porcelain era in 1909. The trend of issuing porcelain plates had

reached the Deep South and would soon spread Westward. By the end of 1909,

twelve states were issuing porcelain license plates, and some twenty cities and

counties had experimented with porcelains as well. The coming decade would

see the era of porcelain license plates rise sharply, reach it’s peak, and decline

to a mere shadow of its former self.

The 1910s

The dawn of the second decade of the 20th Century saw numerous cities,

counties, and states taking up the trend of issuing porcelain license plates to

vehicle registrants. That year, the states of Kentucky, Michigan and Maryland

began their runs of state-issued plates. In Michigan and Kentucky, all varieties of

plates were porcelain, while in Maryland, only the dealer plates were. Cities

jumping on the porcelain bandwagon in 1910 included Hailey, ID; Valley City, ND;

Tulsa, OK; Jacksonville, FL; and Moundsville, WV. With the exception of the

Moundsville plate, interestingly, each of these cities pioneered their respective

state’s experimentation with porcelain plates. Again with the exception of the

Moundsville, none of the states from which these plates were issued ever took

up the task of issuing porcelain license plates themselves, instead leaving the

issuance of such plates up to individual cities. Pine Bluff, AR, as well as

Covington, Lexington and Paducah, KY also began issuing porcelains in 1910.

This decade also seems to have brought about the proliferation of porcelain non-

passenger varieties as well. In Michigan, porcelains were issued to passenger

vehicles, manufacturers, motorcycles, and motorcycle manufacturers in 1910.

After four years of porcelain plates, both Pennsylvania and Virginia also

introduced non-passenger porcelains in 1910 with dealer issues. That same year,

the state of Connecticut introduced livery porcelains, while the city of New Britain

began issuing porcelain plates to the city’s milk dealers. But in spite of this

obvious rise in the issuance and varied usage of porcelain license plates, there

was still not a single state West of the Mississippi that was issuing porcelains of

its own in 1910.

The demand for affordable automobiles was growing with each passing year as

the utility of the automobile was becoming increasingly apparent. In 1913 Henry

Ford introduced the assembly line to automobile manufacturing and changed

motoring forever. No longer was automobile ownership the elite symbol it once

was, as more and more Americans found ways to afford cars which were now

more quickly and cheaply manufactured. Before long, many states would

abandon their issuance of porcelain plates in favor of more cheaply made flat or

embossed metal plates.

But the porcelain era was not dead yet, and in fact, would reach new heights

between 1910 and 1915. In fact, in that 6 year span, 60% of all the state-issued

passenger porcelains ever produced were issued. 1911 saw officially-issued

porcelain license plates spread North to Canada, where the Provinces of Ontario,

Manitoba, and New Brunswick all began their official runs with porcelain plates.

In the U.S., the state of Arkansas also chose porcelain as the material for its first

state-issued license plate. The very first porcelain plates from neighboring

Louisiana also appeared in 1911 as the cities of Alexandria and Monroe began

issuing porcelains. Other cities first issuing plates in 1911 include University City

and Kansas City, MO, as well as Cordell, OK. The earliest dated Mississippi plate

is also a porcelain from 1911, although it is unclear whether this is a pre-state,

some sort of prototype, or perhaps even the state’s first issue. Meanwhile, every

state that had begun issuing porcelain plates at any time prior to this was still

issuing porcelains.

In 1912, cities in Alabama ceased the issuance of porcelain plates and the state

took over with its first of four annual issues. This was also the single year the

state of New York experimented with porcelains, with a large, undated red &

white plate. In Canada, both Alberta and Saskatchewan began their Provincial

runs with dated 1912 plates. In Kansas, the cities of Kansas City and Wichita each

issued their first porcelains in 1912 as well, as did New Orleans, LA; Dayton, OH;

Dewey, OK; Independence, MO; and Morgantown, WV. When looking at only

official state issued porcelain passenger plates, 1913 was the single peak year in

the history of porcelain plates. In this year, 19 different states were issuing

porcelain plates. These states were still clustered in the Northeast, but reached

into the Deep South states of Alabama and Arkansas and as far west as Colorado.

In fact, Colorado’s first-issue 1913 plate made it the first state West of Minnesota

to officially issue porcelains. Indiana and North Carolina also kicked off their

respective state runs with porcelain plates in 1913. Cities joining the porcelain

fray in 1913 included Caney, KS; St. Joseph, MO; Nowata, OK; and Lima, OH. This

was also the first year of relatively long runs of plates from both Manchester,

New Hampshire and Hamilton, Ontario.

1914 & 1915 would also see substantial, wide-spread use of porcelain plates, but

technically, the decline had already begun. 1914 saw porcelain plates finally

reach the West coast as the state of California began issuing plates. Further

North, Seattle, Washington began issuing porcelain plates to commercial vehicles

that same year. 1914 also saw the first issuance of porcelains from places as

diverse as Stamford, CT; Worcester, MA; Rochester, NY; Bangor, PA; Memphis,

TN; Clifton Forge, VA; and the Oklahoma cities of Bigheart, Chickasha, Okmulgee,

and Shawnee. The city of Shreveport, LA and the Louisiana Parishes of St. John

and St. Mary also issued their first and only known porcelains in 1914.

Three states dropped out of the official state-issued porcelain license plate

business in 1914 and two more in 1915. By 1915, in fact, the numbers had

dropped to 1910 levels and 1916 would see a precipitous drop even further as all

but six states abandoned the use of official state porcelains. In this last of the

peak years from 1910-1915, however, porcelains remained popular. Although no

new states or provinces adopted porcelains that year, cities and counties across

North America continued to utilize porcelain. In fact, porcelain jumped more than

2,000 miles to the West as the Hawaiian counties of Hawaii and Honolulu both

began issuing porcelains. Cities such as Ponchatoula, LA; Clinton, MA; Fairmont,

WV; and both Collinsville and Sapulpa in Oklahoma also issued their first

porcelains this year. By the end of 1915, 90% of all the state issued porcelains

ever produced had been made.

In 1916, 9 states that had been issuing porcelain plates the year before ceased

doing so. Interestingly, however, one state that had never before experimented

with porcelains took a shot with a single issue in 1916. This was the state of

Wyoming which decided the next year to go back to embossed metal plates. For

the next 7 years, the state issuance of porcelain license plates dwindled to a

mere trickle before ending altogether. In 1917, North Carolina abandoned

porcelain for embossed metal. In 1918, Rhode Island issued its first non-

porcelain plate in 14 years. And in 1919, the New England states were finally

porcelain-free as New Hampshire became the last hold-out to switch to metal.

The 1920s

The dawn of the 1920s saw two last-ditch efforts to adopt porcelain in the West,

as the states of New Mexico and Washington experimented with the material. But

like Wyoming four years earlier, one year was enough for Washington, and the

state was back to embossed metal by 1921. New Mexico, however, maintained its

confidence in porcelain, issuing plates for four years. The sole torch bearer for

state-issued porcelains once Washington dropped out, New Mexico carried on

the tradition through 1923 when they finally abandoned porcelain for good. The

era of the state-issued porcelain license plate was now over.

City and county issued porcelains were changing as well. The time when local

plates would adorn all of the passenger vehicles in a given city, town, or county

had now passed. Alexandria, Louisiana’s long run of 10 annual issues ceased in

1920. Kansas City, Missouri’s last porcelain plates for automobiles and

motorcycles also came in 1920. And that same year, the final porcelains were

issued by Memphis, Tennessee before the city switched to metal plates. Bisbee,

Arizona’s two year run of porcelains ended the following year in 1921, the same

year that Honolulu issued a porcelain motorcycle plate, marking the last Hawaiian

porcelain of any kind. Other porcelain runs were ending as well. Manchester,

New Hampshire’s 10-year stretch of annual Garbage plates stopped in 1922. The

Teamsters licenses issued by Bangor, Pennsylvania since 1914 finally ceased in

1923. And North Carolina’s rich tradition of city and county issued plates came to

a virtual standstill in 1926. However, porcelain license plates would manage to

hang on for a while longer with a much reduced selection of local issues which

were becoming more and more specialized.

Among the porcelains introduced in the 1920s were Junkman plates from

Stamford, Connecticut; Motor Bus plates from Fall River, Massachusetts; and

Licensed Trucking plates from Providence, Rhode Island. Clearly, the use of

porcelain for license plates was fast becoming a thing of the past. As the decade

wore on, fewer and fewer porcelain license plates would be used.

The 1930s

While there were literally hundreds of different varieties of porcelain license

plates being issued by states, provinces, cities, and counties throughout the U.S.

and Canada in 1915, just 15 years later in 1930, I can only document a grand total

of four porcelain license plates of any kind. Only a few cities were clinging to

porcelain at this late stage, with runs continuing into the 1930s from Worcester,

MA; Wilson, NC; and Providence, RI. The group of plates thought by most to be

from Rochester, NY also continued the issuance of Milk Licenses into the 1930s.

The only two cities known to have introduced any type of porcelain license plate

during this decade were Sacramento, California, which began issuing Wholesale

Produce Dealer plates in 1935, and Schenectady, New York which began the

issuance of Milk Licenses mid-year. In 1937, the 20+ year run of porcelain plates

privately issued to motorists using the Long Island Motor Parkway finally came to

an end, and the end to porcelain license plates altogether was only 10 years off.

The 1940s

The only city-issued porcelain license plates in use in the 1940s were Produce

Dealer and Wood & Coal Dealer plates from Sacramento, CA; Milk Permit plates

from Bristol, CT; and Licensed Trucking and Hackney Carriage plates from

Providence, RI – none of which appear to have continued past 1942. With the

demise of the Providence plates that year, New England’s uninterrupted 40-year

run of porcelain license plates dating back to 1903 finally came to and end.

Beyond these few city issues, Delaware brought porcelain plates back to the

state for the first time since 1915. Issued from 1942 through 1947, these were

multi-year base plates designed to be revalidated annually with metal date tabs.

With the re-introduction of Delaware porcelains, this was the first time a state or

provincially issued porcelain license plate had been used since 1923. Surely we

will find odd porcelains from the 1940s here and there as time goes on, such as

the toppers used by vehicles at the West Point military academy from the mid

1930s until at least 1940, but by the end of World War II, the death knell for

porcelain license plates had been sounded. After 40 years, porcelain had

become a thing of the past.

| 1903 - 1942 1903 1904 1905 1906 1907 1908 1909 1910 1911 1912 1913 1914 1915 1916 1917 1918 1919 1920 1921 1922 1923 1924 1925 1926 1927 1928 1929 1930 1931 1932 1933 1934 1935 1936 1937 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 |